How I Ported the Web to the Web!

Remember web proxies? They were a cool bit of tech that let you browse the web anonymously or bypass censorship without a full VPN. They were popular in the early 2000s, but have mostly fallen out of use today. Here, I'll take a deep dive into how they worked, why they stopped working, and how we built browser.js, a modern alternative that's powerful enough to support today's complex websites.

Traditional Web Proxies

The first major implementations of web proxies were phproxy, CGIProxy, and later Glype. All of these services use the same extremely simple mechanism:

First, the user navigates to https://proxy.com/example.com/. When the server recieves the response, instead of serving a normal static page, it will make a request to https://example.com/ and fetch the contents, recieving some HTML that looks something like this

<head>

<title>Example.com</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://example.com/index.css" />

</head>

<body>

<h1>Example Domain</h1>

<a href="https://example.com/more">more information</a>

</body>

The server performs a simple transform, rewriting all URLs found in the html:

<head>

<title>Example.com</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://proxy.com/example.com/index.css" />

</head>

<body>

<h1>Example Domain</h1>

<a href="https://proxy.com/example.com/more">more information</a>

</body>

And then will send it back to the user as the page they requested. Image resources are fetched and served back verbatim, and POST requests from form submissions are forwarded to the original server as well. Since the links point back to the proxy server, the user can continue to navigate the web through the proxy.

Let's try this in practice. I'm going to set up a server to do this simple transform, and then navigate to the google.com homepage through it.

At first, this seems to work great. We're on our own origin, but it's rendering the google homepage perfectly! However, as we start to interact with the page, things start to break. Interacting with the search bar does nothing, and clicking on other pages causes the page to fall apart even further. Worse, trying to force a search by navigating to google.com/search?q=... immediately flags our request with a captcha that can't be solved.

Back when these simple web proxies were first written, they worked great, letting you have a basically complete browser experience. So what happened?

Javascript

The web has changed a lot since the early 2000s. One of the biggest changes has been the increasing prevalence of javascript. On the google homepage we requested, the search bar, buttons, and most of the interactive functionality is entirely powered by javascript. For most sites today, javascript can't just be ignored like it could.

Unfortunately, javascript presents a serious challenge for proxies. If you look back at the simple HTML example from earlier, it’s possible to understand exactly what it will do at runtime without ever having to load the page. It will request exactly the resources it lists, no more, no less. It cannot self-modify its own behavior, hide its functionality, or change what gets shown dynamically. This is why proxies worked so well across most of the web!

Javascript breaks this guarantee entirely. Anything that can be considered a programming language is basically completely immune to static analysis. As soon as the site loads a script, it’s impossible to tell ahead of time what resources it will attempt to load.

To give you an idea of just how hard this problem is: can you tell what the following snippet of code does?

[][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]][([][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]]+[])[!+[]+!+[]+!+[]]+(!![]+[][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]])[+!+[]+[+[]]]+([][[]]+[])[+!+[]]+(![]+[])[!+[]+!+[]+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]+(!![]+[])[+!+[]]+([][[]]+[])[+[]]+([][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]]+[])[!+[]+!+[]+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]+(!![]+[][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]])[+!+[]+[+[]]]+(!![]+[])[+!+[]]]((![]+[])[+!+[]]+(![]+[])[!+[]+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[!+[]+!+[]+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]+([][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]]+[])[+!+[]+[+!+[]]]+(![]+[])[!+[]+!+[]]+(!![]+[][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]])[+!+[]+[+[]]]+([][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]]+[])[!+[]+!+[]+!+[]]+(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]+([![]]+[][[]])[+!+[]+[+[]]]+(!![]+[][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]])[+!+[]+[+[]]]+([][[]]+[])[+!+[]]+([]+[]+[][(![]+[])[+!+[]]+(!![]+[])[+[]]])[+!+[]+[!+[]+!+[]]])()

This is JSFuck, a "dialect" of javascript that only uses the characters []()!+. It's perfectly valid javascript, but it’s basically impossible to understand what it does without running it.

This is an extreme example, but it shows the complexity at play here. There's no reliable way to tell what a piece of javascript will do before loading and executing it. For proxies, this is a huge problem. If the javascript loads resources from the original domain, the user’s browser will make requests directly to the original server bypassing the proxy, deanonymizing the user and in most cases completely breaking the website.

You used to be able to get away this by just blocking javascript entirely, but as the use of javascript shifted away from progressive enhancement towards "reimplement the entire dom as js objects", this became less and less viable.

Modern Proxies

In browser.js we set out to build a modern web proxy that could handle the complexity of modern web applications.

The first step of making a modern proxy was leveraging Service Workers: A relatively obscure feature to most web developers, it allows the page to deploy a small bit of persistent javascript that runs in the background, independently from the main window. Importantly, a page’s service worker has the capability to intercept and handle network traffic made by the page.

Instead of the page making requests to the backend, it would make requests to itself. The service worker can then route requests through a minimal cors proxy on the backend. By moving away the heavy lifting of parsing and rewriting resources to the client, logic is simplified greatly and hosting a proxy becomes much more scalable.

However, this still leaves the problem of javascript. To deal with this, we need to take a step back and look at what a web proxy is trying to accomplish.

Think of a hypervisor. Its purpose is to "trick" the guest OS into thinking it’s running on real hardware, when in reality it’s running on a virtualized layer. The actual instructions are running on the real CPU, but attempts to access hardware are intercepted and emulated.

We need to do the same thing for the webpage. We need to trick it into thinking it’s running on the original domain, when in reality it’s running on our proxy domain. Any attempts to access resources or information about the environment need to be intercepted and emulated.

In this case the "cpu" is the native javascript engine, and the "hardware" is the DOM and browser APIs.

For most APIs, we can leverage the power of monkeypatching. Since javascript is so dynamic, we can simply overwrite global variables and functions to point to our own implementations. For example, the fetch API is used to make network requests. We can overwrite the global fetch like this:

window.fetch = new Proxy(originalFetch, {

apply(target, thisArg, arguments) {

arguments[0] = "https://proxy.com/" + arguments[0];

return Reflect.apply(target, thisArg, arguments)

}

})

And now calls to fetch will be routed through our proxy, and since the only reference to the original function was overwritten, the page has no way of accessing it. The Proxy object's apply trap is used here instead of a normal function wrapper so that the page can't detect that we've modified the function.

Almost every single web api can be handled this way. Anything that modifies the DOM, makes network requests, or could potentially expose information about the environment needs to be intercepted and properly emulated.

Monkeypatching alone can't do everything though. There are still a few edge cases that need more powerful techniques.

Javascript Rewriting

Let's look at this simple snippet of application code, which many sites will have in some form:

let url = location.href

console.assert(url == "https://example.com", "we’re not running on the expected page?")

This exposes the real origin of the site, breaking our invariant. The trouble here is that this cannot be monkeypatched. The "location" property descriptor of Window is marked as non-configurable, so it can’t be overwritten like others can. If this code is ran, it would immediately break out of the proxy and expose the real origin, no matter how many globals we modify.

However, we don't neccesarily need to run the original code as-is. We control all the resources loaded onto the page, since they all pass through the service worker and the proxy, so we can modify the code before it runs.

And while it's true that javascript can't be truly statically analyzed, what we can do is insert hooks during static analysis that allow us to inspect and modify runtime behavior. This method, referred to as "JS Rewriting" is the most powerful technique for building modern web proxies.

After parsing the syntax tree of the loaded script, we can search for Identifier tags that hold "location" and start replacing them.

The snippet above will be rewritten to this sandboxed version:

let url = $proxyWrap(location).href

console.assert(url == "https://example.com", "we’re not running on the expected page?")

The critical part about this is that proxyWrap knows the original value and can still pass it through if needed. If a variable named location happened to be shadowing the real location, the wrap would know not to replace it.

Property access must be handled similarly: A piece of code like

let href = window["loca" + "tion"].href

Can be safely rewritten to

let href = window[$proxyProp("loca" + "tion")].href

And the property access can be redirected at runtime to point to the emulated one. With powerful rewrites like these, even extremely obfuscated and complex pieces of code like the JSFuck example will be properly handled. The only issue with this approach is that AST parsing can get expensive. Especially since many modern sites load javascript bundles in excess of 5MB!!

Here’s where Rust and WebAssembly step in: with the amazing oxc project and clever optimizations, we were able to reduce the time it takes to rewrite by >10x, making the overhead almost unnoticable for most webpages.

Through a combination of instrumentation through rewriting and monkeypatching globals, we can ensure that webpages' javascript will always go through our sandbox and be handled properly. With everything implemented, we finally have a web proxy that's able to take on the challenges of the modern web!

Privacy

The other major issue with traditional web proxies is the lack of data protection. Since the backend needs to rewrite web content, it’s also able to log or modify any data that passes through it.

The service-worker based approach makes it better, but all traffic will still eventually go through a server that can see everything in plain HTTP.

For a web proxy to be truly private, it needs to be end-to-end encrypted between the browser and the target server. This means only encrypted data would ever be sent through the server.

There's a unique challenge here though. We can't just invent some new encryption scheme, because the target server needs to understand it. It's end-to-end, and the server end only speaks HTTPS/TLS over TCP.

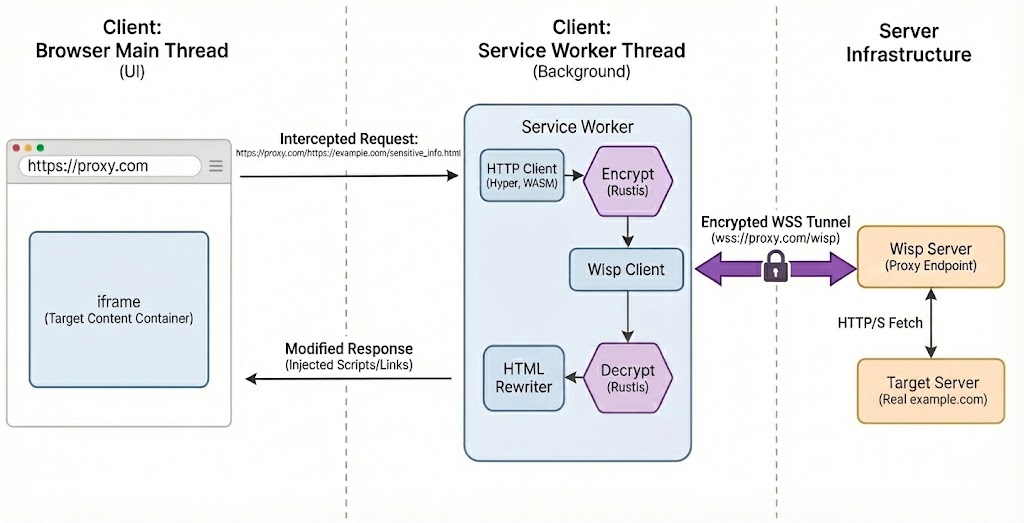

Sending TCP is easy, the Wisp Protocol allows our web page to speak raw TCP over a websocket forwarded to the server, but the TLS part is tricky.

The browser already ships with a full cryptography stack, including TLS, but other than the severely limited WebCrypto API, it's not exposed to javascript. This ultimately means that we're going to implement our own TLS stack at the javascript layer.

Fortunately, this isn't as hard as it sounds, and leveraging Rust's WebAssembly toolchain again, we were able to run rustls in the browser with surprisingly low overhead, with requests coming close to native speed.

Our stack now looks like this:

You can try out the live demo here.

Free, Serverless AI and Cloud

Start creating powerful web applications with Puter.js in seconds!

Get Started Now